Columbus history: Schiller Park before it celebrated German influence

German Village’s popular Schiller Park celebrates the neighborhood’s German influence by honoring one of the country’s most famous poets.

It hasn’t always.

This May will mark 100 years since the park was renamed Washington Park amid anti-German sentiment during World War I, a sort of precursor to the modern controversy over the appropriateness of Confederate monuments.

Just as there is opposition to honoring the likes of Confederate Commander Robert E. Lee, who took up arms against the U.S., there was hostility a century ago toward all-things German, including Schiller Park’s namesake, Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller.

“There was a great deal of re-naming during the war,” says Kathleen Neils Conzen, Thomas E. Donnelley Professor Emeritus in the Department of History at the University of Chicago.

Passing a renaming ordinance on May 27, 1918, Columbus City Council wrote, “This nation is now at war with representatives of the ideas sung by the poet Schiller.”

In distancing Columbus from Germany, local schools abolished German language classes, German newspapers were shut down—even speaking German was forbidden.

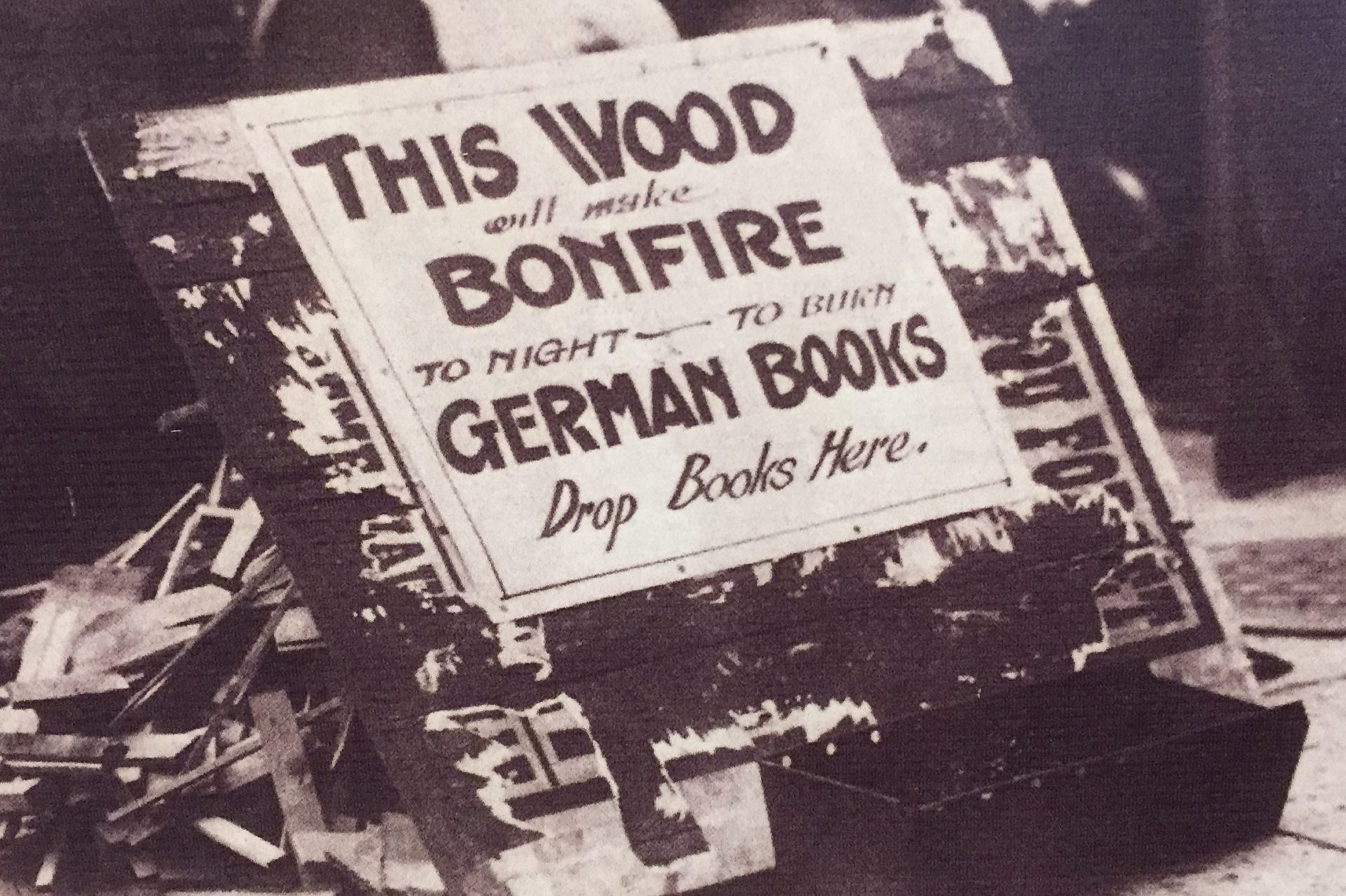

In the park (originally dedicated in 1867 as City Park), German books were burned at the foot of the famed poet’s statue. Some residents were said to have lobbied, unsuccessfully, for the teardown of the monument, erected in 1891.

Columbus, of course, wasn’t alone in its vitriol.

President Theodore Roosevelt denounced “hyphenated Americanism,” as in German-American, saying Americans must pick a side as the country waged war in Europe.

It wasn’t until April 7, 1930 that Columbus City Council voted—unanimously—to change Washington Park back to Schiller Park, reversing an act of war “hysteria” to no opposition from the more than 200 people in attendance, according to the Ohio State Journal.

“The thing that I think is so ironic about it is Schiller was a man of such vision, about humanity, and about freedom and liberty,” says Katharine Moore, executive director of the Jefferson Center for Learning and the Arts, who formerly served as executive director of the German Village Society. “He was the wrong guy to pick to have issue with.”

One casualty of the ephemeral German-American opposition was Schiller Street, still known today as Whittier Street; city officials in 1930 declined to change the name back, suggesting it would hurt businesses with identities tied to Whittier. (Edison and Lansing were once known as Germania and Bismarck, too).

More significantly, Columbus and other cities dealt with the matter differently moving forward.

“The lack of such visceral reaction during World War II in part reflects the more sober judgment of American public opinion that the reaction during the previous war had not been justified,” says Conzen, who specializes in immigration and ethnicity, along with nineteenth-century social history.

Nonetheless, debates reminiscent of the city’s Schiller controversy are still taking place 100 years later, as Americans grapple with how to recognize history with parks and monuments.

Last summer in Worthington, a sign marking the home of Confederate General Roswell Ripley was taken down amid fallout from violence in Charlottesville.

Around the same time, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs elected to maintain monuments at the Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery in Columbus’s Hilltop neighborhood.

“Having witnessed what happened last summer with the Confederate statue issue, there is a tremendous sense of relief that our (Schiller Park) statue is of someone we can feel such unreserved admiration for,” Moore says.

By Evan Weese / Originally appeared in (614) Mar 1, 2018

BROUGHT TO YOU BY