The Secret Life of James Thurber: CMoA pays tribute to the Columbus humorist

There’s a cartoon by James Thurber that sums up the work of author and 40-year Thurber historian, Michael J. Rosen. In the cartoon, a woman receives an eye exam while a doctor points to a line of letters on a classic eye chart. From several feet away, the woman replies, “Certainly I can make it out! It’s three seahorses and an ‘h.’ ”

“I love the woman’s benighted confidence, and how Thurber suggests that our perceptions are always a bit off,” Rosen explains. “Mine have always been, and I’ve harnessed that for much of my work.”

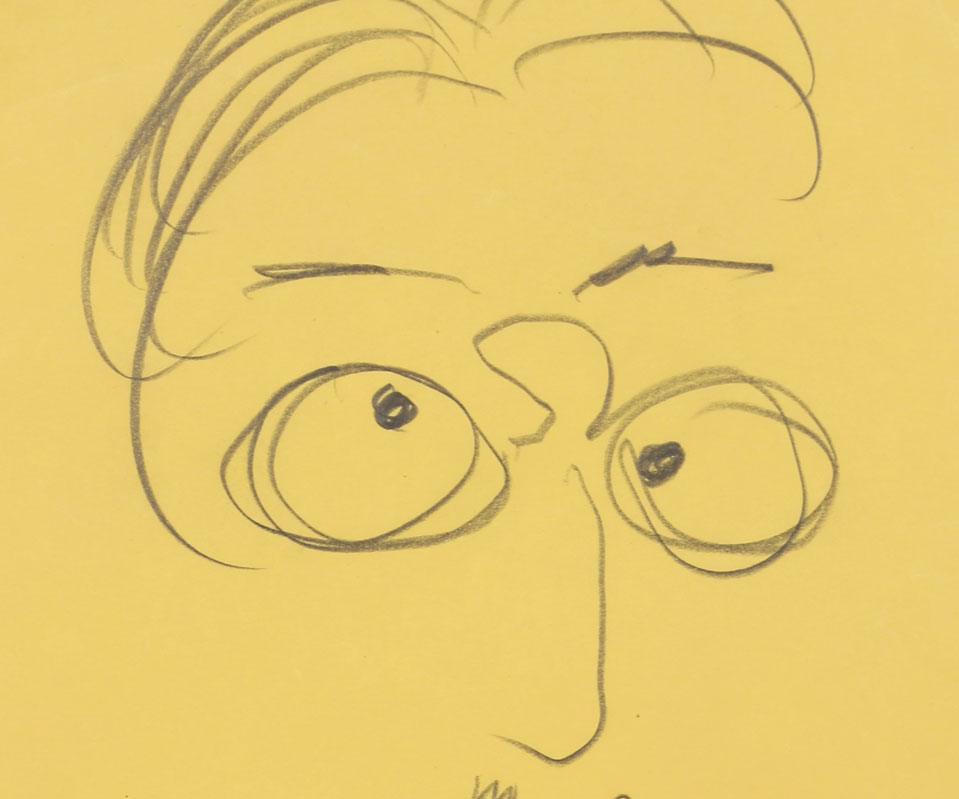

Perhaps you’re familiar with Columbus-born humorist James Thurber from the Thurber House—the home he rented for a period of time which is now a haven for writers-in-residence and literary programs for all ages. But for Rosen, it’s his second home. As former literary director of Thurber House, Rosen’s fascination with Thurber’s legacy is unwavering, to the point that he can recollect key drawings, stories and facts with episodic memory. In correlation with what would be Thurber’s 125th birthday, Rosen is prepping the book release of A Mile and a Half of Lines, an extensive look at Thurber’s artwork that rede ned American humor and cartooning. Thurber’s work will also be exhibited under the same title at the Columbus Museum of Art, reintroducing viewers to his twentieth-century influence.

With access to all of Thurber’s images, both published and unpublished, Rosen proposed the notion of the Mile and a Half exhibit in 2015. As Thurber was known to spontaneously draw on scraps of notebook paper, his art was never used with archival consideration.

“I wanted some plastic, inimitable, vintage Thurber that people would know, and I wanted to present a great deal of imagery that people didn’t know,” Rosen says. “So, 125 years after his birth, [Columbus Museum of Art] agreed it was high time to claim James Thurber as one of Ohio’s great artists and one of the nation’s most important creators of the cartoon. Here we are with nearly one hundred drawings appearing at the museum for six months.”

Some exhibit guests may discover that Thurber succeeded Mark Twain in terms of following the humorist pedigree, while others may learn that he was an artist who was almost rendered entirely blind (which prevented him from graduating from Ohio State University.) The crux of Thurber’s drawings evolved from 1927 to 1941, as he attempted to draw with a giant magnifier with white ink on black paper, while lacking some of his sight.

BROUGHT TO YOU BY

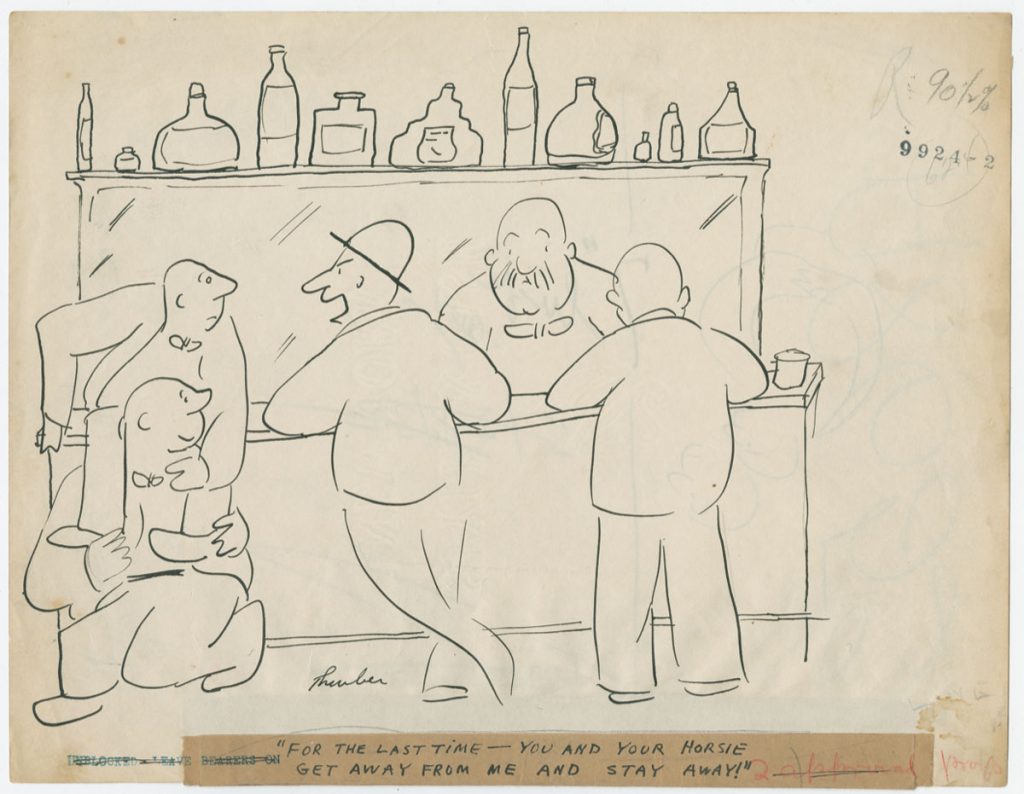

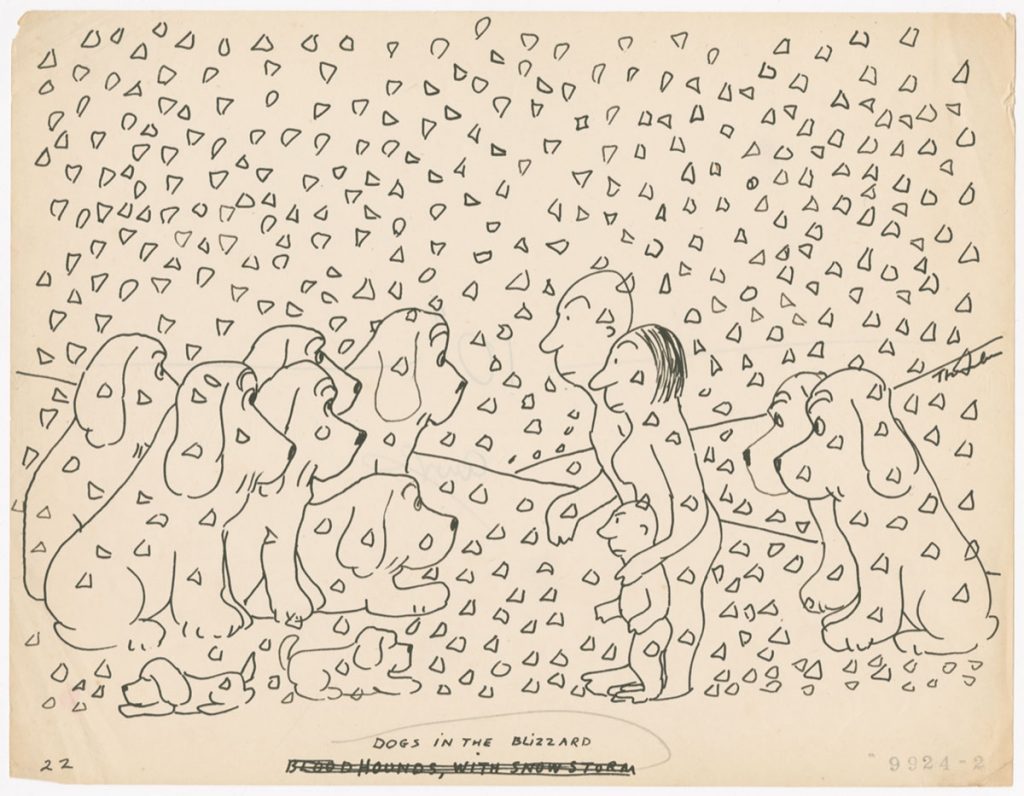

Unlike many artists in the late period who works in watercolors and oils, “Thurber’s output is exclusively done as spontaneous. He in many ways invented the idea of an unstudied line in art,” Rosen says. “Before Thurber, [a] cartoon was a very well-drawn image, usually with two or three lines that provided to humor. Thurber was the first to draw not beautiful pictures, but the pictures were funny themselves, and the captions dropped to just one phrase or one line. When we think of Twain, we think novels, maybe some essays, things that are in the canon because they’re big. Thurber wrote an enormous variety of different forms in which his art take shape.”

As Thurber lived through Prohibition, the Great Depression and the Cold War, much of his work, while humorous, is based upon resilience. Politically active in the 50s when he was red listed as being a “communist sympathizer,” Thurber declined to accept an honorary degree from Ohio State, as the university prevented free speech on campus. Considering humor as a vital force of the human condition, Rosen regards works in A Mile and a Half of Lines as relevant and engaging, with all viewers approaching the exhibit with different motives.

“It’s both the fact that he was an astonishingly polished wordsmith as well as having the heart of humor at the center of his work, which is, ‘something’s wrong and humor is a mechanism of coping,’ ” Rosen says. “Art helps us translate our experience because it’s in a different medium. There’s appeal for families and then there are those who will look at the cartoons and recognize the poignancy.”

So would James Thurber detest modern technology at 125 years of age? Rosen doesn’t think so, in fact, the real-time social media age would make for good material. “Back in the sixties, he was writing about the culture going at such a fast pace, words were blurring that we couldn’t keep up with things. News was daunting, language was eroding at such a fast pace because of people skipping and being sloppy. I mean he would be writing about the fact that right now, no one does one thing at a time,” he says. “Our information overload has exceeded the capacity of the brain. As a jittery, jumpy person—as he often describes himself and his generation—he would need the tools of humor and the art of writing all the more.”

Throughout his life, Thurber’s influence ventured beyond Columbus, but as A Mile and a Half of Lines resides at the Columbus Museum of Art for six months, Rosen hopes that Thurber’s work finds its way home. “Perhaps his best known work was the autobiographical vignette of My Life and Hard Times, then during his more grim period, he returned to Columbus in his imagination, researched and wrote The Thurber Album, which are portraits of people that were dear to him,” Rosen says. “He’s famous for saying that the clocks that chime in his dreams are the clocks of Columbus.[…] Columbus remained very much the sketchbook on which he could draw.”

A Mile and a Half of Lines: The Art of James Thurber, will be on display at Columbus Museum of Art from August 24, 2019 through March 15, 2020. Visit columbusmuseum.org for information.

BROUGHT TO YOU BY