Interview: Columbus native Hanif Abdurraqib on his New York Times best-seller

At the time of my deadline, Hanif Abdurraqib’s third book, Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to a Tribe Called Quest, had just debuted on the New York Times’ best-seller list. For the Columbus author it was unexpected, but for fans of Adburraqib’s poetry and essays, it was necessary. His observations and critiques of popular culture and a generation of youth entrenched in instant gratification is a pulse that is impossible to ignore, or put down. His prose has become a mirror reflecting the zeitgeist with heart-breaking honesty.

Those looking for a firm timeline of events in the career arc of the hip-hop collective A Tribe Called Quest, or salacious tour stories, or extensive interviews, are not going to find them in Go Ahead in the Rain. When finished reading you will certainly feel like you’ve assembled a grand knowledge of a group that Abdurraqib gushes was responsible for a sound that “shifted the direction in hip-hop” by offering “alternative windows into the world of samplings, cadence, and language,” but more so, you begin to understand their greater importance in his life as a guide, a cultural touchstone.

Abdurraqib is the only talking head, and many times he’s only talking about his past, his adolescent abandonment of the trumpet, the dynamics of his high school crew, a physical altercation with his older brother, or the various ways one can make Kool-Aid. Elsewhere he searches for answers from his favorite group in personalized letters to each member, knowing they won’t likely be answered.

In many ways, these literary devices, and the deftness with which Abdurraqib structures them to tell this story of fandom, are parallel to those windows that Tribe were opening since their debut in 1990. I recently spoke with Abdurraqib to get some insight into the making of the book and why A Tribe Called Quest was the perfect point from which to launch his fascination with obsession.

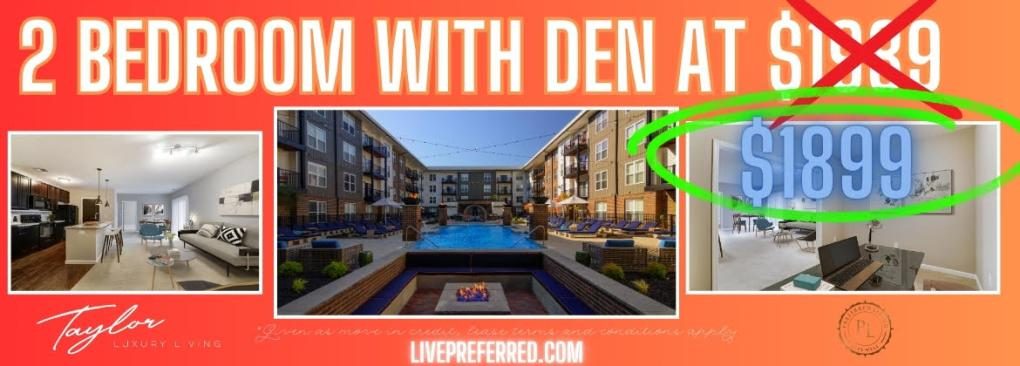

BROUGHT TO YOU BY

KJE: Was the book originally going to be a straight biography? When did you realize that it was going to become something more personal, and less traditional?

HA: Early on I wanted it to be a biography and I didn’t know any other way to write about the group. But I think biographies are written with the artist in mind; they are the vehicles to tell the history. In order to do that well, the writer has to be an expert, and in order to [be an expert] the writer needs to have countless hours with the group, or loads and loads of archival footage. I was confident I could do that, but realized I wasn’t writing the book for the group, I was writing it more for myself, and my own examination of the absurdity of fandom—or what it means to live a life tethered to your affection for a group of people you’re never going to meet or actually know.

You get very deep in your attempts to interpret what this group was doing musically and thematically, but you temper it with your own history and experiences—so it works. I love how you even apologize for over-analyzing or “loving” the music so much. Is there a word for that? Is that your job as someone who writes about music?

I wouldn’t say that’s my job per se, but I think most of my obsessions are driven by a curiosity to force me to excavate meaning out of the things I love. Music, film, or art in general; if I truly love something I’m driven to make sense of it in a way that will allow it to have a lasting life beyond my immediate consumption. With so much music now, and with so much popular culture, things are consumed and then forgotten. Part of what the whole project of writing this book was—was to build out a history that could be touched, that could be looked back on, that could be part of a grander conversation. So I’m not just writing about Tribe, I’m writing about how they sit in the world, how their music also populated the world around me, how they responded to the world and how the world responded to the music. I’m building an ecosystem.

There’s a kind of eulogy in the book for rap’s golden era with the advent of sample clearing. Do you feel like there’s been an era since that’s on par with ‘88 – ‘93, when Tribe were at their pinnacle? As hip-hop is something that is always adapting, what to you sounds innovative in the same way today? What do young people making music have to do to create that same connective tissue that Quest created?

Kids are doing it in different ways. For a lot of young rappers today, they are at their best when they are playing reporters of their moment. That’s something I think A Tribe Called Quest were essentially doing, or perhaps N.W.A. was doing more explicitly. Vince Staples’ latest album, FM, struck a chord with folks because beyond the fact that the rapping was good and the production was good, underneath that the narrative was bringing to life a very specific feeling, and a very specific place, where if you have never been to that place physically, you can close your eyes and be transported to it. It was very much like what The Chronic did for me growing up in Columbus with not a lot of relationship to the West Coast. I did not know what a ‘64 Impala looked like, but listening to that album I could visualize it.

As much as you know about them and reflect on them and adore them in this story, are you at all worried that Q-Tip, or the others are not who you think they are? Something about, meeting your heroes?

No one is who we think they are. I’m barely who I think I am. That’s the thing I kept thinking as I was writing this book is how wild it was that I had built this huge affection for people I don’t know. How fandom is all about projecting whatever you need onto the creations of people who you’ll never speak to. My hope with this book is of course that people will fall in love with Tribe like I did, but also grasp how to articulate their own complications with fandom, and how to work through that. We’re at a very real point, particularly in film and music, where people are asked to work through their allegiance to celebrity, and their allegiance to the celebrities they love. I’ve seen some really exhausting and frustrating missteps on that, particularly around R. Kelly. What I set out to do was write about how fleeting all of this shit is, how fleeting fandom is, and how fleeting fandom can be. It’s about how to know when an attachment to an artist who is building an architecture for your life is vital, but also to know when that artist is no longer yours, and being able to let go.

For more information about Go Ahead in the Rain, and Abdurraqib’s forthcoming work visit abdurraqib.com.

BROUGHT TO YOU BY