North Market Past: A history of the 143-year-old business

Contrary to what some might expect, the North Market has outlasted a history that’s pitted culture and economics against it. It has, through dedicated merchants and customers, endured.

Columbus’ three other public markets can’t say the same. The Central Market, the East End Market House and the West End Market House have all risen and, ultimately, fallen over the decades. That leaves the North Market as the only space through which the city can preserve and celebrate this aspect of the area’s history.

“This place has been evolving since the day it opened in 1876,” said Rick Harrison Wolfe, executive director of the North Market Development Authority. “Everything changes. The merchants changed, the way people shop changes, the buildings change. … We are an evolving thing, and that’s the only way we’ve been able to survive over these 143 years.”

Columbus was incorporated as a city in 1834, and the first public market was born a little over 10 years later: the Central Market, built around 1850, stood on Fourth Street between Rich and Town Streets. If that location rings a bell, it’s because today, that is the location of the Greyhound Bus Station.

At the time—before the era of supermarkets—public markets were a place for Columbus residents, farmers and merchants to buy and sell fresh food and other products. This was a national trend according to the Ohio History Connection, many cities were building public markets “to facilitate agricultural and industrial as well as retail trade around the middle of the 1800s.”

The Central Market House became “one of the best-known institutions of Columbus,” with blocks of stalls lined with horses and wagons where three mornings during the week and Saturday nights it was “a very busy scene,” write Lyan Liu and K. Austin Kerr in their book The Story of Columbus: Past, Present and Future of the Metropolis of Central Ohio.

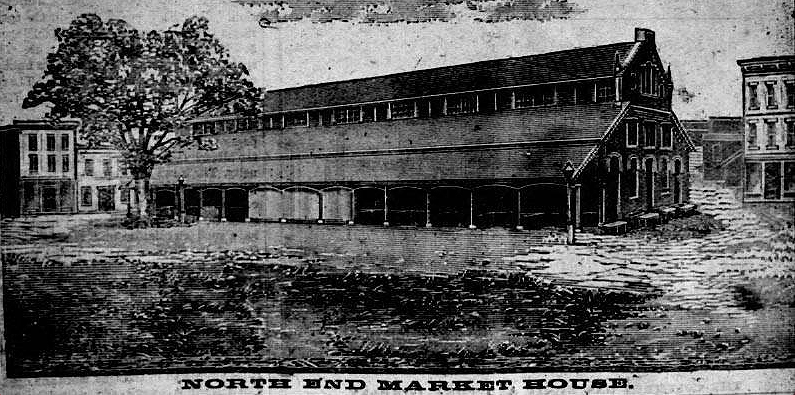

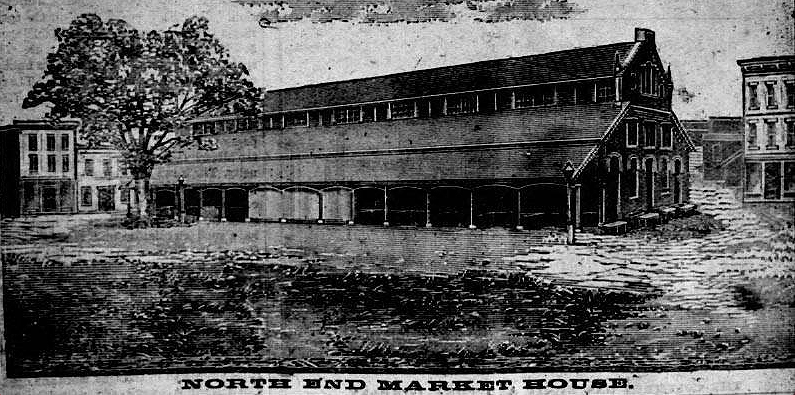

The two other now-closed markets, the West and East End Market Houses, were built following the Central Market House, and in 1876, the North Market opened on Spruce Street.

The land upon which the North Market sits has a story that precedes the historic space. It was Columbus’ first cemetery, the Old North Graveyard, dating back to 1813. The cemetery remained in use until 1873, growing to more than 12 acres and becoming the final resting place for some of the city’s founders, including Columbus’ second mayor, who was buried there in 1823, according to Jannette Quakenbush’s book Columbus Ohio Ghost Hunter Guide.

But times, and Columbus, changed, and the city needed to make room for the future. Columbus’ first railroad station was built next to the cemetery, and as it grew throughout the 1850s and 1860s, the railroad companies led lawsuits to acquire more and more of the cemetery’s land, Quakenbush writes. In the end, many—though not all—of the Old North Graveyard remains were transferred to Greenlawn Cemetery.

BROUGHT TO YOU BY

The original North Market was a two-story brick building. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the market had a slate roof and was 325 feet long and 80 feet wide—distinctly different from its space now. The neighborhood in which the North Market was built was undergoing a massive transformation in the late 19th century, becoming a hub of commercial and warehouse buildings and reflecting “the growth of Columbus as an important retail and distribution center after the Civil War,” according to the Ohio Historic Places Dictionary. It’s perhaps fitting, then, that the market would eventually come to occupy one of those old warehouses after an incredibly turbulent and uncertain period in the market’s history.

By the mid-20th century, public markets were losing their popularity, and a fire at the East End Market in 1947 put an end to one of Columbus’ four markets. Just a year later, the North Market itself burned down. To revive the market, its merchants pooled their resources and purchased a military-surplus Quonset hut. In contrast to the market’s previous building, the Quonset was a metal, arch-shaped building meant to be a temporary space.

However, as the remaining markets went out of business— the original Central Market was demolished in 1966—the North Market limped along.

“That was maybe the 50s or 60s, as public markets were starting to struggle, and we were city owned and city operated up until the late 80s,” Wolfe said. “Generally speaking, that’s not in this day and age the best way to do it.”

The market was losing money, but as the last one standing at a time when people were once again becoming interested in markets and their vendors, the city, merchants and shoppers decided to create the North Market Development Authority in an effort to reinvigorate the space.

The NMDA in partnership with the city and community partners was key in transforming the North Market into its modern iteration. In 1992, the city purchased a former Advanced Thresher warehouse adjacent to the Quonset hut. It was a space with “an interesting interior structure of wood and steel, abundant windows to provide natural light so lacking in the old market, good vertical and horizontal clearances to enable movement of crowds, and a second level of office, restaurant and dining space,” as the AIA Guide to Columbus describes. In other words, the foundation in which the current North Market resides could be built. The North Market moved in 1995.

“There was no arena, there was no convention center. All the buildings on Park Street were boarded up,” Wolfe said. “It took the support of the city, and individuals and some of our corporate friends around to keep this thing alive.”

When Wolfe became the NMDA executive director in 2013, he says he wanted to get the market out of more than 100 years of operating in the red. Continued investment from the city has been vital to make that vision a reality.

“We have to be subsidized, and we also have to be creative on how we make money,” Wolfe said.

The North Market may be the only remaining public market in Columbus, but two others still exist in Ohio: one in Cleveland and one in Cincinnati, Wolfe says. It’s not even the only place in Columbus people can go for a reminder of this piece of Columbus’ history; a new restaurant called the Central Market House is named in tribute to “the thriving Central Market which served as the central economic center of Columbus from 1850 until 1966,” according to its Facebook page. However, the market is a must-see for Columbus residents and visitors, presenting a one-of-a-kind microcosm of the city’s food and cultural scene, and it’s a storied space that Wolfe himself is partial to.

“The Short North … COSI, the art museum, those are all amazing resources and amenities to our city. But you know, we’re free to hang out. I think we’re the best out of all those. I think we’re the best.”

BROUGHT TO YOU BY