Maker’s Space

The power of hair gives life and meaning to April Sunami’s soulful pieces

Many cultural traditions hold hair as sacred—a symbol of strength, virility, beauty, wisdom. In Native American, Southeast Asian, Rastifaran, and African cultures, letting hair grow and be in its natural state is a symbol of one’s connection to the Earth itself. Even western tradition acknowledges the connection of hair to strength as told through the story of Samson and Delilah.

And, as in the case of the biblical Samson, governments have used shearing aboriginal people’s hair as a way of stripping their power, identity, and connection to their cultural heritage. In 1902, Commissioner of Indian Affairs William Atkinson Jones commanded all Native Americans living on federal land to cut their hair and denied rations to those who did not comply with the orders.

“In this world, for me personally, I’ve always had this feeling that I had to be small, avoid conflict. All these women in my canvas, they are stand-ins for me. They get to be brave.”

April Sunami

Black hair has been no less politicized in this country and the history of trying to strip one’s culture through controlling hair is not in the distant past. As recently as February 2020, 18-year old student Deandre Arnold made the news when he was suspended from school for wearing locs.

For artist April Sunami, the politicization of hair was what brought her to start thinking about incorporating it into her own art.

“When I started with this theme of hair, I decided to wear my hair in locs. At the time it was symbolic. It was not accepted in corporate environments and for me it was a statement about going all in as an artist,” said Sunami. “[Hair] has so much to do with who you are, how you want to be seen, how you see yourself, and that was the jumping off point. It started off me just playing with color and being expressive but the meaning has evolved over time into me trying to say more with it and using different materials to represent themes in history, mythology, and spirituality.”

The spiritual significance of hair is at the core of every painting she creates.

“The hair is about soul. It’s a physical manifestation of something spiritual, something deeper,” she said.

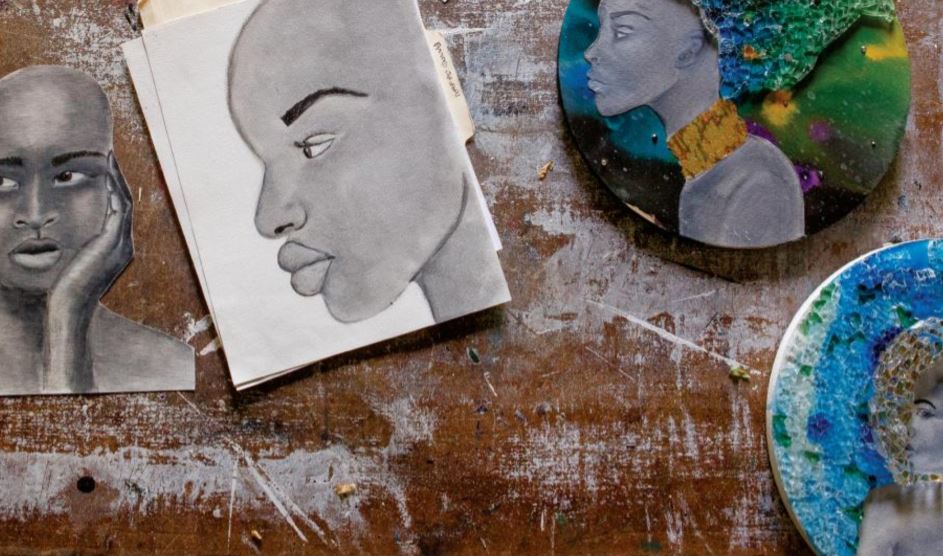

She paints hair in bold acrylic swaths, gives it texture with cowry shells and paper beads, and brings it to life with shattered glass found at the side of the road.

“I am a collector of history,” said Sunami. “Beads, stone, wood, bullets, break-away glass… I put it all in my artwork.”

Each object she uses has a story to tell, some she already knows, some she can only guess at. Sometimes she enlists her children to gather objects she finds, sometimes friends save things they think she might use. When Queen Brooks, a renowned artist, community elder, and old friend and mentor accidentally shattered her shower door she didn’t sweep the pieces up and throw them away; instead, she saved them to be woven into the locs of a woman on one of April’s canvases.

“The subject has always been women,” Sunami said. “The women are kind of a stand in for myself. They are the reference point for understanding the world, a gateway to empathy in trying to understand someone else’s experience.”

BROUGHT TO YOU BY

When you walk into her studio at the King Arts complex, where she is currently an artist in residence, the billows of three-dimensional hair leaping off the canvas are the first thing you notice, followed quickly by rows of piercing eyes. Many of the subjects stare straight out of the canvas and into your soul, a style she was warned about by an art gallery owner years ago as an art taboo that would never sell. She promptly ignored their advice. And for good reason. These steady eyes invite you to stand present and match the gaze; to look at the face of each woman in the canvas and connect with her, acknowledge her. In some sense, it is Sunami’s way of defying “the inequity and invisibility of black women.”

“Through my gaze they are powerful. They are active, not passive subjects,” she explained.

For the same reason, she often embeds mirrors into her canvases.

“The viewer can take away whatever they want to from the art, but you can’t help but see some part of yourself there too and feel empathy for someone else’s hurt, someone else’s struggle,” Sunami said.

“In this world, for me personally, I’ve always had this feeling that I had to be small, avoid conflict. All these women in my canvas, they are stand-ins for me. They get to be brave. They get to be strong and stand their ground and be fully who they are. Through these paintings I get to find my voice. The art is where I put all of my defiance and strength.”

BROUGHT TO YOU BY