The Pandemic Life

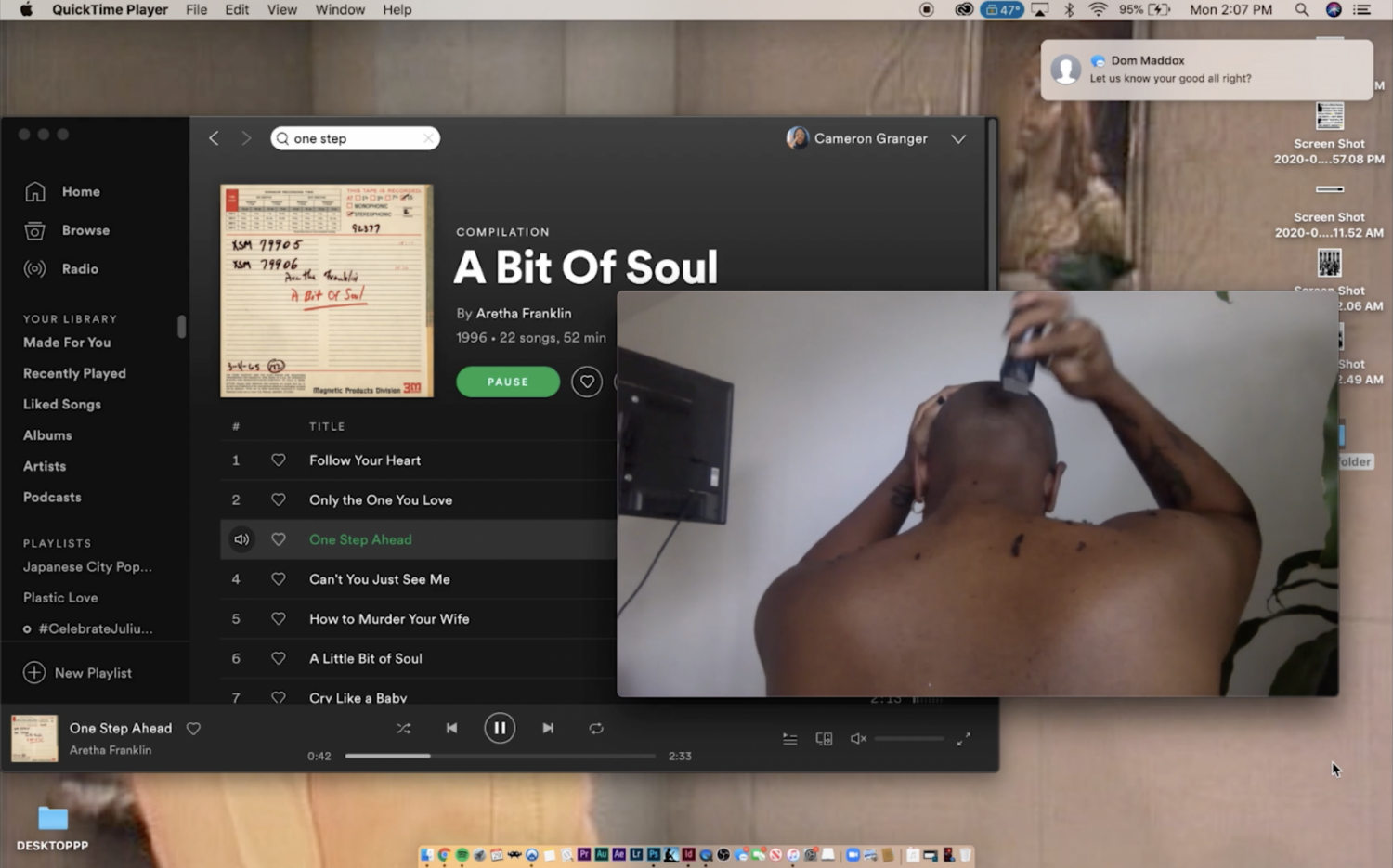

Wex Center artist Cameron Granger claims his own narrative during COVID

When local artist, filmmaker, and cultural critic Cameron Granger was invited by the Wexner Center for the Arts to contribute to its Cinetracts ‘20 program, he was thrilled to be producing art among artists he admires. Then the world changed when the pandemic struck, affecting his mindset, process, and priorities.

Stuck in New York City, Granger was unable to come home to Columbus to work alongside his chosen family in the place to which he feels connected. “I was in a different headspace than I was when I accepted the project,” he said. “So I had to figure out what I was going to do there.”

“I don’t like to make work from a reactionary place. I don’t feel like that’s my story to tell or that my work would be of service to those narratives. I try to make something that is coming from my personal point of view first.”

Certainly, the filmmaker, whose work often revolves around notions of blackness, would have plenty of relevant and timely material to draw from, given the growth of the Black Lives Matter movement, the subsequent nationwide protests, and the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color. However, Granger said he wasn’t interested in explicitly making something about the protests or COVID.

“I don’t like to make work from a reactionary place. I don’t feel like that’s my story to tell or that my work would be of service to those narratives. I try to make something that is coming from my personal point of view first,” Granger said. “Honestly, like, not to say I do not have a stake in the protests—they are literally protesting for my existence—but I didn’t want to show up like that.”

Granger’s work is highly personal. He has collaborated with his mother, Sandra, on a body of artwork that includes a piece dedicated to his grandmother, Pearl. Other work includes an experimental piece inspired by stories of black youths slain in his hometown of Cleveland, Ohio.

As his deadline for Cintetracts ’20 loomed, Granger’s mind weighed heavy. Living the pandemic life meant slowing down, giving him an opportunity to reflect and study, which he said has been his primary work of 2020.

Although not his plan, he filmed his contribution on his laptop from the studio apartment he was subletting in New York City and focused on what he was feeling and studying. He had been doing some reading on Black people and their history of being redacted, and it was hitting close to home.

As his following on Instagram grew, so did his discomfort. “I had all these new white people who were looking to me to perform my Blackness for them. I felt really uncomfortable that I couldn’t exist in the way I wanted to. So I wanted to hide. I was thinking about redaction as a way to control my own narrative to protect myself from that violent gaze,” he said.

BROUGHT TO YOU BY

Besides that film for the Wex, Granger said he hasn’t really felt compelled to make much this year. The pandemic has helped him realize that he needed to change the way he was working.

“I hope that one thing to come from this period of time is that we can all find ways to disinherit this really oppressive and heavy work ethic that we have inherited from capitalism,” said Granger. “It’s the belief that you always have to be working or producing your hardest at all times. You don’t have to do that,” he said. “In early March and April when there were many virtual discussions with artists, I thought ‘This is so stupid. People are literally dying. Why do I care about what a curator has to say?’”

Granger said he felt limited in his practice and made a bold choice to shift his work as an artist so that he could make room for more community work that he cared about. He also realized that even while in New York, he could make an impact at home in Columbus. With that came the idea for the Get Free Telethon, a 24-hour livestream in July with performances, readings, film screenings, cooking demonstrations and discsusions to raise funds for Black Queer & Intersectional Collective, Healing Broken Circles, and Columbus Freedom Coalition.

“Get Free was a big epiphany for me. I thought that I have these platforms, I know these people and I have access to these spaces. I can use this to support the work that I want to support. It wasn’t thinking about it as making art at the time, but it is communal art, public art. That’s what I am trying to do to— make more room in my practice toward that,” Granger said.

However, Granger says the most important work anyone can undertake right now is to take care of themselves. “If I do nothing else but workout and eat something good, I think that’s a total accomplishment. It’s all about sustainability. I’m claiming that for myself.”

As galleries begin to fill their calendars again and shows go up, he says, “for better or for worse, I am trying to make sure that when things start up for real that I am in a place where I feel healthy and ready to jump back into it.”

BROUGHT TO YOU BY