How a one billion year-old boulder was uncovered from a Columbus backyard

As a young man in the late 1800s, John Scatterday tried time and again to dig up the large rock buried in his parents’ lawn near Sixteenth and Waldeck Avenues, in the University District. But he never managed to remove all the dirt from around it. In 1905, road crews began hitting the same rock while building Iuka Avenue. Rather than try to remove it, the men decided it would be easier to just re-route the new street slightly to the west. Out of sight; out of mind.

But not for long. When it came time to build sidewalks along the new street, workers were forced to deal with the situation again. Using construction equipment and brute force, the men unearthed what turned out to be a huge boulder weighing 15 to 20 tons.

The spectacle caught the attention of Dr. Edward Orton, Junior, Dean of the School of Engineering at The Ohio State University. He thought the boulder would make an excellent tribute to his father, Dr. Edward Orton, Senior – a noted geologist who had been among the first teachers hired at Ohio State and who, beginning in 1873, served as the university’s first president.

BROUGHT TO YOU BY

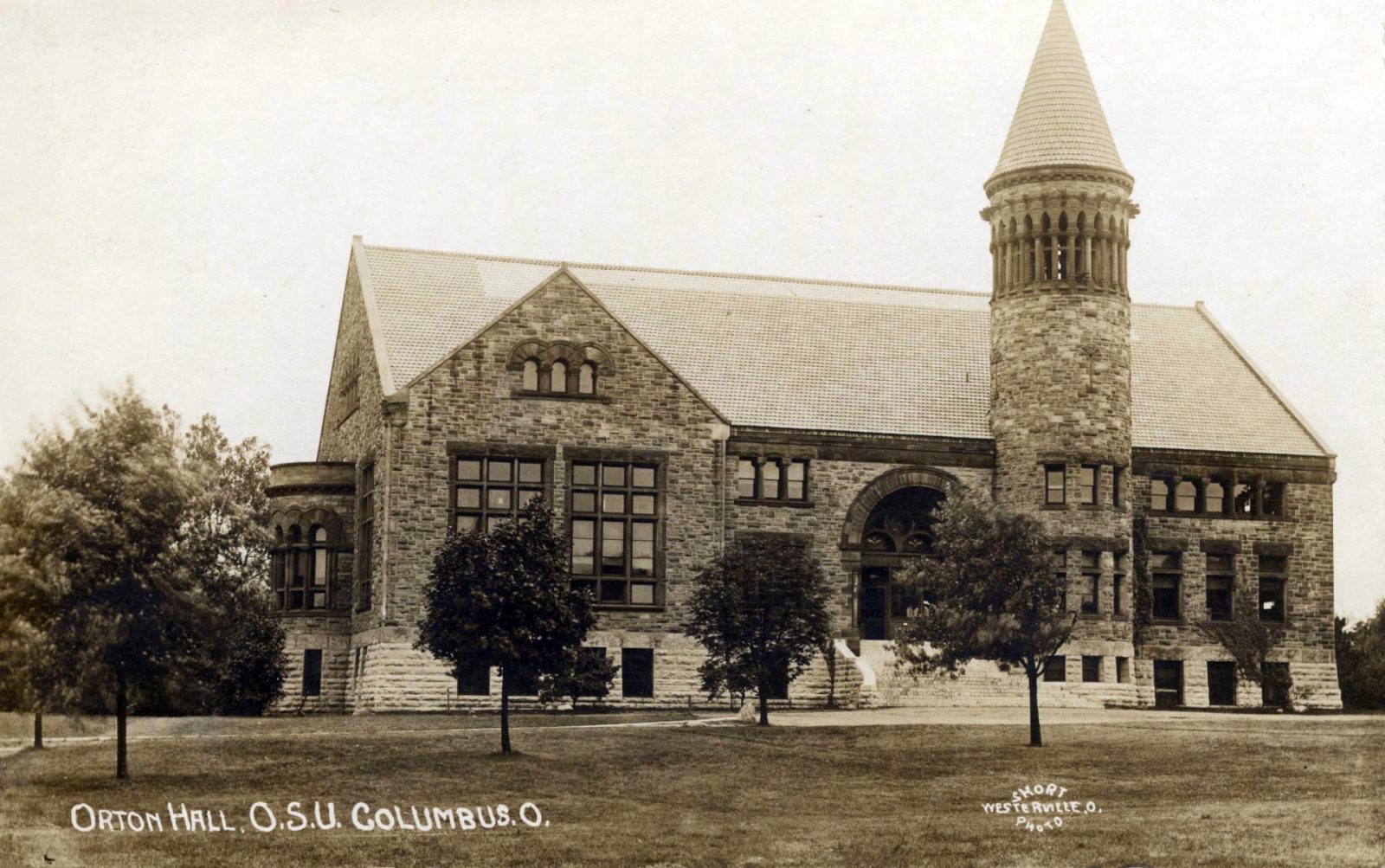

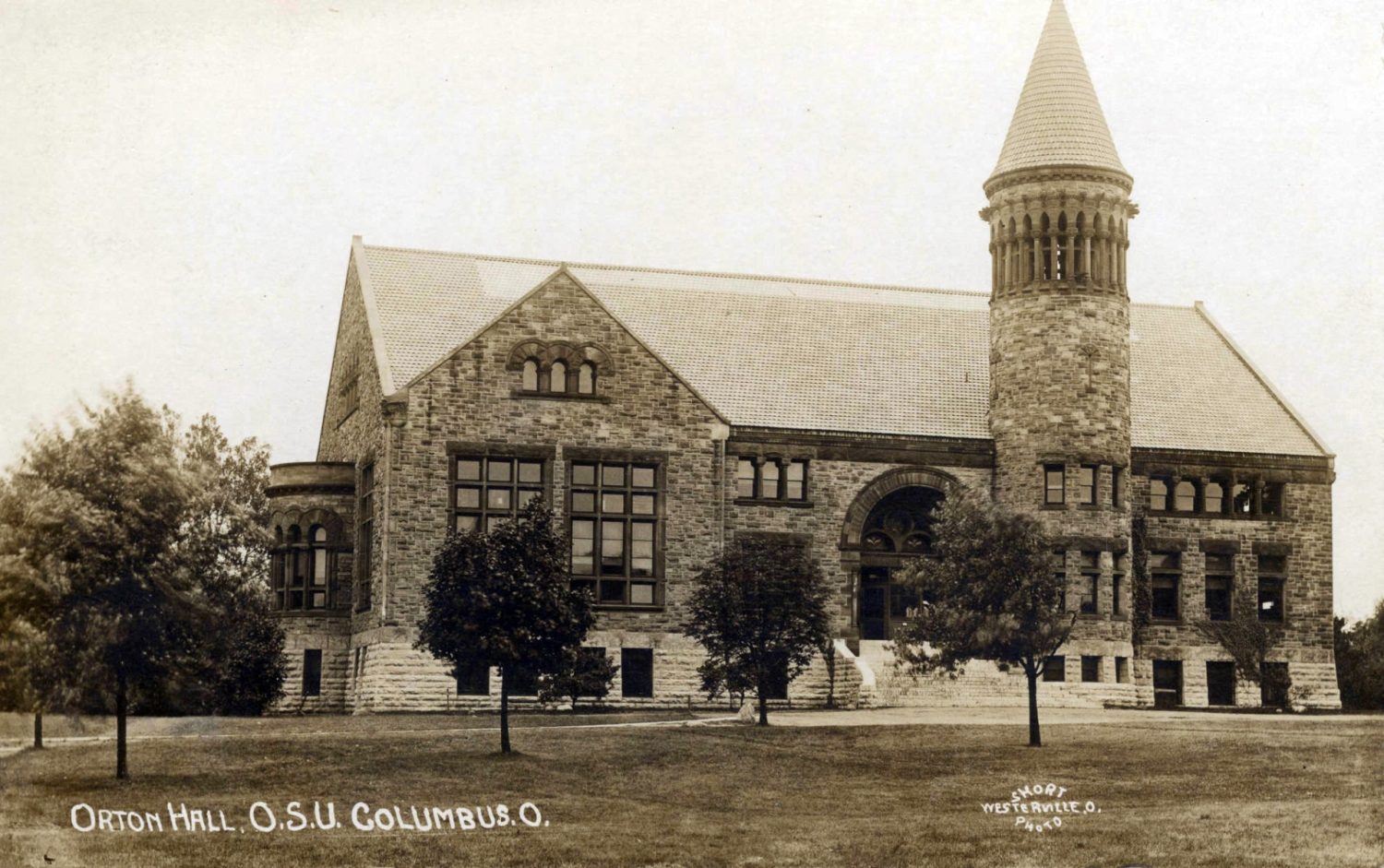

Like his son, Orton Senior was, first and foremost, an expert in rocks. He was Ohio’s state geologist from 1882 until his death in 1899. His contributions to the field of geology were many, and OSU honored him in 1893 by naming its new geology building, Orton Hall, after him.

Orton Junior made a deal with the road crew to take the rock off their hands. He hired a man with a wagon and eight sturdy horses to move it about a half-mile southwest, to be placed at the northwest corner of Orton Hall on South Oval Drive. History is not clear whether Orton Junior or the Geology Department was to pay for the transfer. Regardless, once he had the rock on site, the mover demanded more money. He said he had not counted on it being so heavy and that the extreme weight had broken his wagon. Orton told the man that a deal was a deal, and that if he didn’t like the terms they had agreed to, then he was welcome to return the boulder to the construction site. The rock stayed.

For the younger Orton, it was plain to see that the boulder was an “erratic” – an ancient rock from Canada that had been carried here by glaciers tens of thousands of years ago. Just how ancient became clear in 1971, when testing by the OSU geology department set the age of the rock at just over one billion years old. Erratics come in all shapes and sizes, and they’re not particularly rare. But given the opportunity to display a fairly large erratic next to his father’s namesake building, the younger Orton was quite pleased with his endeavor.

Orton Hall, itself, is something of a geological oddity. The university’s second-oldest building was constructed in 1893, using 40 different types of Ohio stone. The rocks in the outside walls were laid as they appear in nature, with the oldest in layers at the bottom and the youngest at the top. Near the top are 24 decorative columns, each made with a different type of Ohio stone. And above the columns are 24 gargoyle-like representations of prehistoric animals. Orton Hall was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1970.

As a side note, Ohio State has another connection to glaciers. Dr. Thomas C. Mendenhall, professor of physics and mechanics, was the first teacher hired at Ohio State, making him a contemporary of the senior Orton. Mendenhall became known across the country for his engineering achievements and, in 1892, Alaska’s Mendenhall Glacier was named in his honor.

John M. Clark is a Columbus historian and author. You can find his work regularly in (614) Magazine.

Want to read more? Check out our print publication, (614) Magazine. Learn where you can find a free copy of our new January issue here!

BROUGHT TO YOU BY