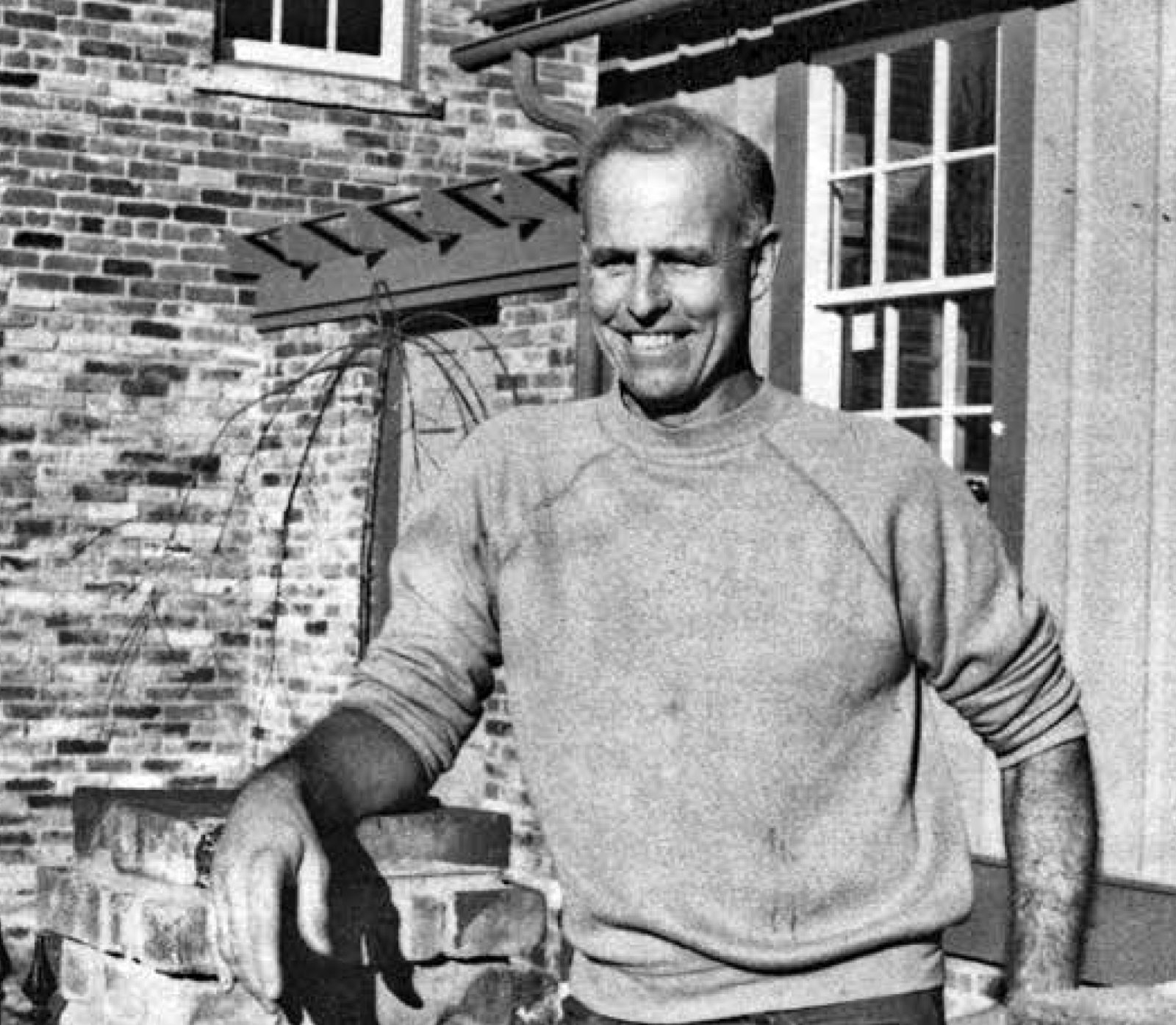

Neighborhood Pride: How the late Bob Hurry helped shape the German Village we know and love today

It was 1961 when Bob Hurry, a bright, ambitious geophysicist from Texas, purchased a rundown home in German Village at the corner of E. Beck and S. Grant.

At the time, Hurry paid $3,000—a sum that even back then wasn’t much for a house. In 2007, according to real estate records, it sold for $560,000, and is valued today at over $800,000.

While not all of this can be credited to Hurry (Bill Lenke, Steven Shellabarger, Bob Eckel, and more, were part of its storied development as well) it is fair to say that exactly none of it—and none of the updates to the numerous other homes in the area he took on—would have happened without him, according to historians.

Sarah Marsom, creator of the Gay Pioneers of German Village Tour, said the neighborhood was actually one of the city’s more undeveloped neighborhoods when Hurry first moved there in the 1960s.

BROUGHT TO YOU BY

Hurry himself commented on the state of the neighborhood in a December 1981 article in The German Village News about his work saying, “When I first moved here, the area was so bad that friends who were transferred here with me refused to visit me after dark.”

Marsom noted that Frank Fetch went by a different name at the time: dogshit park. “It was essentially just a vacant lot then,” she said.

But none of this could stop Bob Hurry.

In fact, according to John Clark, local historian and author of German Village Stories Behind the Bricks, many have postulated that it was because of Hurry’s sexual orientation that he—alongside several other trailblazing individuals—chose German Village to begin with.

“The way I understand it, buying cheaper houses in rundown neighborhoods to fix them wasn’t something that many people did back then,” Clark said. “But a lot of the gay men who helped develop the area did so to avoid being harassed, since German Village at the time was an accepting neighborhood. It became known as the first real gay neighborhood in Columbus.”

And once Hurry did establish himself restoring homes in German Village, he didn’t stop. He ended up making a full-fledged career of it, working well into the 1980s. He was prolific, and nothing short of an expert, eventually refurbishing so many homes in the vicinity of Grant and Beck that this area became known as Hurryville, or Hurry’s Corner, according to historians.

One of the many abodes he updated—located on S. Grant Ave. between Jackson St. and Berger Alley—saw him convert a building that was originally built as a livery stable into a home that still catches eyes in the neighborhood today, through the addition of beautiful street-facing gothic windows and an entirely new wing.

And even though Hurry passed in 1987 due to AIDS, his impact on German Village can’t be underestimated, both as a champion for the Columbus gay community in the area, and tireless home developer.

According to Clark, Hurry helped author large portions of the German Village Guidelines—strictly-enforced building codes that determine what renovations can and cannot occur to help maintain the area’s unique historic appeal.

“They’re sort of the Bible for restorations in German Village,” he said. “If someone wants to change anything to their home, they’re going to be looking at the German Village Guidelines.”

And as much as we count his documented, brick-and-mortar contributions to one of the city’s most iconic neighborhoods, it also feels as if something about his pioneering spirit lives on in the German Village we know and love.

So next time you’re walking through its weathered brick streets, or past a row of its historic homes, if one happens to catch your eye just a little more than the others, stop. Take it in for just a minute. That might be Bob you see.

Learn more about the history of German Village at germanvillage.com

BROUGHT TO YOU BY